Southwest Minnesota State University

Men's Swimming & Diving

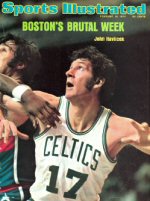

Sports Illustrated Article

Read about the Southwest Swim Team in

Sports Illustrated

Big Fish in a Small Pond

No kazoo tooters can compete with Southwest Minnesota State, which features a pep band, video-taped pep talks and stereophonic Strauss.

By Jerry Kirshenbaum

Feb. 18, 1974

Swimming may be small potatoes elsewhere, but the Golden Mustangs of Southwest Minnesota State College inspire such affection in Marshall (pop. 10,000) that radio station KMHL has taken to beaming important meets to the housewives and soybean farmers. Because stroke-by-stroke coverage tends to pall, Sportscaster Maynard (Gabby) Weiss is obliged to live up to his nickname. Resourceful though he is, Weiss once ran out of words during a 1,000-yard race; in desperation he had to switch back to the station for a few polkas.

Fortunately, Southwest Minnesota's swimmers give their announcer more to talk about with each passing season. Just six years old, Southwest got into the swim in 1970 and has compiled a 43-12 dual-meet record the last three years. Several of the losses have been to the likes of Minnesota and Iowa, and last season the Golden Mustangs upset Nebraska, a feat diminished only slightly by the fact that the Big Red is pale pink in swimming. While not yet ready to overtake such small-college powers as Simon Fraser and Claremont-Mudd, Southwest is 11-2 this season and, after finishing 25th a year ago, could crack the Top Ten at next month's NAIA championships.

"I promise you one thing," says the school's president, Jay Jones, "if we do well, there will be an incredible outpouring of emotion here." Behind that pledge lurk frustrations that have built up ever since the Minnesota legislature created Southwest to inject fresh life into the state's moribund farm belt. The college was a boon to Marshall, a neighborly, elm-shaded town surrounded by cornfields, one of which became the site of the $40 million campus. Southwest's ambitious little theater now delivers culture to the countryside, and class buildings are linked by passageways designed to accommodate wheelchairs, a feature that attracts handicapped students. With low red-brick buildings looming against the gray horizon, the college has a stark beauty reminiscent of Brasilia. But Southwest suffers the same remoteness that causes diplomats to consider Brasilia a hardship post. Owing to the enrollment squeeze felt by small colleges generally, its student body, 3,200 three years ago, has declined to 2,100, and on Fridays the campus empties as students head out onto State Highway 19 to hitchhike home for the weekend.

Southwest students try to find diversion in sport, but here, too, there is a depressing sameness. The school has groaned through six straight losing football seasons. It has yet to win its first track meet. Its baseball team only recently recovered from a 0-18 ordeal. Doggedly, the student body cheers the boys on, a loyalty rewarded earlier this season when Southwest's basketball team finally snapped a 46-game losing streak.

In this desert of defeat, the swimming success seems almost a mirage. The credit goes to Don Palm, the 35-year-old coach who uncovers athletes overlooked by larger schools and then enlists their undying devotion. A case in point is co-captain Rich Jones, a breaststroker from suburban Chicago who has stuck it out at the Minnesota college for four years. "I can't hack it in a small town like Marshall," Jones admits, "but if I had tried to leave, Coach would have talked me out of it. He has a way about him."

For a lad like Jones, the Southwest pool beckons as a clean, well-lighted place on the forbidding prairie. The $1.25 million facility boasts underwater windows, an automatic scoreboard and a separate diving well, and Palm runs an efficient program. Far from being a bloodless organization man, however, he gets so uptight at meets that he has to leave it to others to punch the stopwatches. He also gets weepy at team meetings, and is so anxious to please that he recently siphoned 10 gallons out of his car's gas tank at midnight to accommodate the visiting father of a team member.

"Some coaches say they don't care if they're liked as long as they're respected," Palm says. "I want to be liked, too. I don't see how you can have team unity and spirit otherwise."

To further improve morale, Palm enlivens home meets with pageantry that suggests there is still some corn left in the old cornfield. On hand are cheerleaders and a pep band as well as a corps of Timettes, two dozen coeds who perform timing chores at meets. There is also a pre-meet ceremony that begins with the pool in darkness. Suddenly a shimmering light reveals the Southwest team, resplendent in white sweats, lined up at pool-side. As the lights gradually brighten, amplified theme music from 2001: A Space Odyssey blares forth. The crowd's frenzied reaction to all this—the 550-seat pool is very often SRO—leaves little doubt that the young school is as starved for ritual as it is for conquest.

Despite these flamboyant touches, Palm owes his success to his thoroughness. When he was hired in 1963 to organize a team at his alma mater, Bemidji (Minn.) State College, he mailed letters to 1,200 high school coaches in the Midwest, dragnet recruiting that yielded surprisingly good catches. Four years later Bemidji was runner-up in the NAIA, at which point Palm gave up his swimming job to concentrate on his duties as the school's football coach. "Quitting after finishing second in the country—how dumb was that?" he now asks rhetorically. Three losing football seasons provided the answer. "I realized belatedly that swimming was my sport," he says.

In 1969 Southwest was about to launch its swimming team and Palm signed on. Southwest's pool was not yet ready, which gave him the luxury of a year in which to do nothing but recruit. One reason for the new school's poor athletic showing was its lack of alumni to provide aid, a deprivation that led Marshall citizens to organize a Mustang Boosters Club to raise scholarship funds. Palm's first-year take was $1,500 (it has since grown to $4,500) and he logged 20,000 weary miles to find high school prospects on which to lavish that paltry sum.

Because of Palm's willingness to go far afield, nearly half of his team hails from outside Minnesota. From Wyoming, improbably, have come six Southwest swimmers, including freestyler Dave (Cowboy) Broyles, who holds six school records. "The University of Wyoming coach sent somebody to talk to me," Broyles relates. "He couldn't be bothered to see me himself. And here Coach Palm drove all the way from Minnesota. I was impressed."

Besides giving Southwest a winner, Palm established a summer swimming camp. He also started an aquatics concentration in which phys ed majors take lifesaving, scuba diving and a course in stroke mechanics called aqua-physio-dynamics. In 1972, before his own school was accredited to compete in them, he brought the NAIA championships to the Southwest pool. His enthusiasm for swimming infected Marshall residents. An AAU program was launched and Marshall High School, untroubled that the nearest competition was 90 miles away, organized a team, too. As the swimming craze spread, Southwest students found themselves vying with townspeople for seats at Mustang meets.

Seldom has the Southwest pool been jammed more fully than it was for a recent meet with Eau Claire (Wis.) State. Eau Claire finished seventh in the NAIA last year and Southwest fans seemed to feel that a victory would go a long way toward compensating for past humiliations. In the charged atmosphere Southwest butterflyer Mike Fallon refused to share his dormitory room with his younger brother Mark, who swims for Eau Claire. As for Palm, he video-taped a five-minute pep talk and played it to the swimmers before the meet. "I knew I'd be too choked up by then to talk in person," he said.

Wary of the pep band, lights-out ceremony and the rest, Eau Claire Coach Tom Prior outfitted his swimmers with kazoos. They tooted them at poolside during the meet—but who listened? As Southwest's fans shouted themselves hoarse, the Mustangs won, 65-48.

There remained the danger that Southwest, having peaked for Eau Claire, would have trouble getting up for the NAIAs, but Palm said, "We'll be ready." Also prepared is Gabby Weiss, who announced the Eau Claire meet with the help of two color commentators and taped interviews. Thus, while Dave Broyles was winning the 1,000, Weiss was able to play remarks that the Southwest star had recorded earlier. Not a bar of polka music was heard.